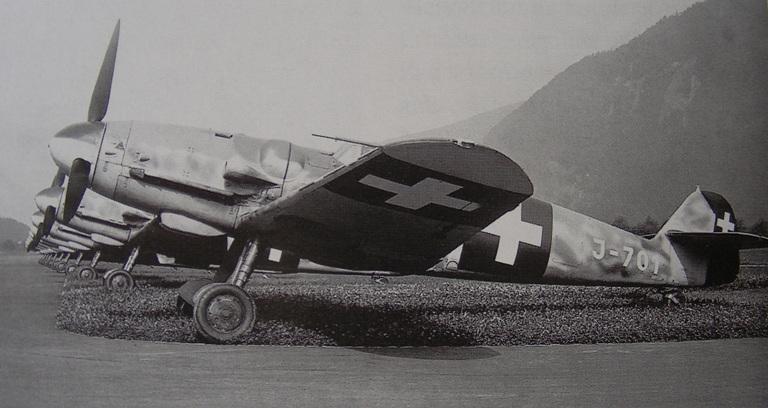

On June 4, 1940, and again on June 8, German Bf-110s met Swiss Bf-109s, and five of the twin-engine destroyers were shot down. Then the government of the Swiss Confederation backed down. Joseph Goebbels was outraged. On the night of June 6-7, 1940, the Minister of Propaganda first noted in his diary notebook, "The neutral foreign countries are eating out of our hands." Then, however, he added: "Only Switzerland remains steadfastly insolent, has shot down two planes for us, we have done her four in return, and she has also received a sharp note." Why was Hitler's confidant so agitated? Outside Switzerland, the episode is virtually unknown, yet the events of early June 1940 were relevant, indeed formative, for the Swiss Confederation's subsequent conduct in World War II. On May 10, 1940, the Wehrmacht had begun its attack on France - in defiance of the expressly declared neutrality of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. The attack also caused fears in Switzerland, which was also neutral, because what was to prevent the Wehrmacht from bypassing the French Maginot Line not only in the north but also in the south via the canton of Basel-Land? From the northern Swiss cities of Basel, Bern and Zurich, many people fled to central or western Switzerland. General Henri Guisan, the supreme commander of the Swiss army, spoke of a "wave of panic". In this situation, German and Swiss fighter planes repeatedly met in the airspace between Bern, Besançon and Mulhouse. As early as May 10, Lieutenant Hans Thurnheer of Fliegerstaffel 5 fired at a Heinkel He-111 that was in Swiss airspace and resisted the call to land. Who fired first remained unclear. This first confrontation remained without consequences. Then, on the evening of the same Friday, Walo Hörning and Albert Ahl shot down a Dornier Do-17; it crashed on the German side of the border. Six days later, the Luftwaffe then lost a Heinkel He-111 over northwestern Switzerland; the bomber crashed at Kemleten, northeast of Zurich. In the early summer of 1940, the Swiss Air Force had a little more than 200 operational aircraft, of which barely a hundred were reasonably modern fighters, namely German Messerschmitt Bf-109Es and French Morane-Saunier D-3800s manufactured under license - most of them, however, without radios. This did not deter the German Luftwaffe, which could deploy more than 3,000 aircraft in the French campaign. On June 1, 36 He-111s of Fighter Wing 53 flew over northwestern Switzerland. Two Swiss fighter planes, flown by Captain Jean Roubaty and Lieutenant Alfred Wachter, shot down one of these bombers at about 4:20 pm. The plane crashed near Lignière in the canton of Neuchâtel; the five-man crew was killed. A little over an hour later, at about 5:40 p.m., a formation of another 24 He-111s flew over Swiss territory. Once again, Swiss air defenses intervened. A German airborne radio operator reported to his comrades, "Attention, don't shoot, they are Messerschmitts, so own fighter protection!" Only when the five Swiss Bf-109s opened fire did the Germans realize their mistake. One Heinkel was hit so badly that it had to make an emergency landing in Oltingen, France. The incidents now became more frequent - the following day, an He-111 already hit over France managed to escape into Swiss airspace, but was attacked here by a patrol of Bf-109s and sustained additional damage. The bomber crash-landed near Ursins in the canton of Vaud. Hermann Göring was furious. The Luftwaffe chief sent a punitive expedition over Switzerland on June 4, 1940. the Neuchâtel Jura in a circle - a deliberate provocation. A total of 16 Swiss fighters, mostly Bf-109s but also some D-3800s, took off to intercept the German force. Air combat ensued, and for the first time it was Messerschmitts against Messerschmitts. The Bf-110 proved to be clearly outgunned - it was not maneuverable enough to avoid the fire of the Swiss Bf-109s, and not fast enough to outrun them. Over France, the twin-engine fighter had still been superior to enemy Morane-Saunier 406 (the original French version of the Swiss-licensed D-3800) and Dewoitine D.520 aircraft; now that was reversed. The details of the dogfight cannot be accurately reconstructed; in any case, by the evening of June 4, one Swiss Bf-109 pilot was dead, and two Bf-110s had crashed on French soil. Berlin reacted with a sharp note of protest, saying, "The Reich Government expects the Swiss Government to express its formal apology for these outrageous occurrences and to compensate it for the damage to property and persons that has been caused. For the rest, the Reich Government reserves the right to do anything further to prevent such acts of aggression." But on June 6, this time Swiss flak again shot down a German aircraft that had violated airspace, and on June 8 there was another confrontation between Bf-109s and Bf-110s. A formation of the twin-engine fighters attacked a Swiss reconnaissance plane of the obsolete K+W C-35 type. Lieutenant Rodolfo Meuli and First Lieutenant Emilio Gürtler did not stand a chance. But then 15 fighters soared, mostly Bf-109s. In the ensuing air battles, the Swiss Messerschmitts shot down three Bf-110s - a disaster for Goering. Hitler now took matters into his own hands, after - depending on how you count - nine to eleven German planes lost, and made a massive threat. Switzerland buckled. On June 10, 1940, border surveillance flights were stopped, and three days later Guisan banned active air combat. Foreign aircraft were only to be attacked in self-defense; insignificant violations of airspace were no longer to be reported at all. The 17 German pilots interned in Switzerland were released - a clear violation of the 1907 Hague Convention, which required a neutral country to intern foreign troops until the end of the war. But the German victory over France, unexpectedly quick and unexpectedly clear, was a strong argument. From then on, Switzerland pursued a twofold policy: on the one hand, (almost) all the wishes of the Third Reich were fulfilled, on the other hand, General Guisan had a fortress built in the high Alps, the Réduit. Here, in case of a German invasion, the Swiss army was supposed to retreat and offer resistance. This never came to pass.

Source: Welt.de, Johann Althaus